Tisha B’Av is a Jewish day of mourning and shares some similar Jewish mourning traditions to that of losing a family member. “Tisha B’Av” means “the ninth of Av,” indicating the ninth day of the Jewish month called Av. In 2023, Tisha B’Av begins at sunset on July 26 and ends at sunset on July 27.

Israel and the Jewish people have known more than their reasonable share of persecutions and tragedies throughout time. While such events have occurred across the calendar, it’s extraordinary how many tragic events have befallen Israel on the ninth of Av.

Most significant are the destructions of the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem. The First Temple was destroyed in 587 B.C.E. and the Second in 70 C.E. One year later, on the same date, Roman armies leveled what remained of the Temple, leaving only what today is called the Temple Mount.

Jewish tradition says that the long line of calamities occurring on the ninth of Av all started back in the wilderness when Moses sent out 12 spies to survey the Promised Land. It is believed that they returned on the ninth day of Av, and 10 of them gave a frightening report that persuaded the people against going into the Land to possess it. As a result, the generation that left Egypt was not allowed to enter the Promised Land. The Israelites remained in the wilderness, wandering for 40 years until everyone over 20 years old at the time of the spies’ report passed away.

Tisha B’Av

As a day of mourning, many Tisha B’Av observances align with Jewish mourning traditions practiced when we’ve lost a family member. Shared customs for these sorrowful occasions include abstaining from bathing, washing, shaving, and wearing makeup; not wearing leather or fine clothing; refraining from work and anything considered joyful, luxurious, entertaining or celebratory. Like those who have lost a family member, on Tisha B’Av, we sit on low stools as a sign that our hearts have been brought low. We also recite the Mourner’s Kaddish, a traditional declaration said in every synagogue service.

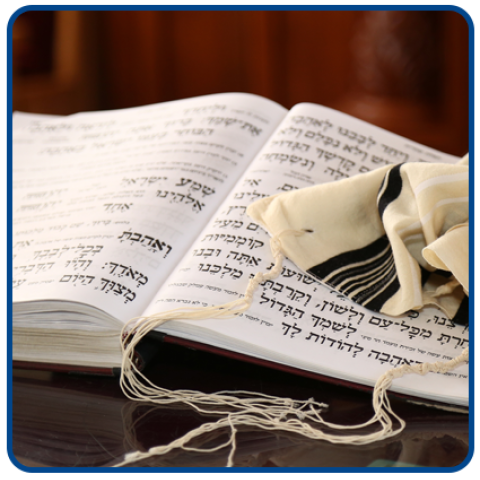

Tisha B’Av mourners do not wear their tallis (prayer shawls) or tefillin (Scriptures wrapped around the forearm or forehead) during the morning synagogue service on Tisha B’Av. Studying the Torah is forbidden when mourning because it is considered a joy. The exception on Tisha B’Av is reading from Lamentations, a book of sorrowful writings in the Hebrew Scriptures. Additionally, on Tisha B’Av, we fast and recite woeful poems called kinot.

Jewish Mourning Traditions

In Judaism, there are several stages in the mourning journey. The time from death to burial is known as Aninut. Jewish tradition calls for burial to take place within 24 hours of the death when possible, and the burial marks the beginning of additional distinct phases of mourning: shiva lasts seven days from burial; sheloshim lasts 30 days from burial; 11 months of mourning are required of those who have lost a parent; and yahrzeit marks the anniversary of the death.

Shiva

The mourning period called shiva begins immediately after the burial and lasts seven days. Shiva means seven. Usually, only the immediate family “sits shiva,” meaning the deceased's spouse, parents, children or siblings. Shiva takes place in the home of the deceased or an immediate family member, and those who engage in it are not permitted to go outside for seven days. Family and friends bring meals and pay condolence visits. The tradition requiring mourners to sit on very low stools during shiva visits has resulted in the common phrase “sitting shiva.”

Jewish mourning traditions vary by branch of Judaism and how strictly the mourner observes their religious practices. Typically, mourners sitting shiva wear black clothing or a torn piece of black cloth pinned to their garment. The fabric’s tear or “rend” symbolizes the biblical practice of rending one’s clothes in lament and sorrow. Sometimes a mourner will place a tear in their clothing near their heart.

Some branches of Judaism observe the practice of covering all mirrors in the home to remove any focus on one’s own appearance. Along these same lines, Jewish mourning traditions forbid those sitting shiva from cutting their hair, shaving, bathing, or wearing fresh clothes, cosmetics, lotions or perfumes. Nor do they wear leather shoes during shiva, as it symbolizes luxury.

Mourners sitting shiva also do not:

- Go to work or conduct business

- Play or listen to music

- Participate in entertaining or celebratory experiences such as parties, concerts, movies, reading or marital relations

- Study Torah – because it is considered a joy to do so

The Mourner’s Kaddish

One of the most important Jewish mourning traditions is reciting the Mourner’s Kaddish, a declaration of God’s holiness. The Kaddish is said three times a day during shiva, sheloshim and the next 11 months and is also said on each anniversary.

Jewish custom requires that the Kaddish be said among a minyan, or quorum, of at least 10 Jewish men. One explanation for this requirement is that the Kaddish was written incorporating a community context, using the word “your” often in speaking to others and including a congregational response of “Amen” at various points.

During shiva, family and guests gather around the mourners to recite the Kaddish. Since the Kaddish is said at all three daily Jewish synagogue services, during sheloshim and the 11 months, mourners often attend services and join others.

One benefit of saying the Mourner’s Kaddish is that it affirms that God is in control and deserving of our praise even in the midst of sorrow.

The Mourner’s Kaddish

Glorified and sanctified be His great name in the world, which He created according to His will.

May He establish His kingdom during your lifetime and during the lifetime of all the house of Israel, speedily, yes soon, and say, Amen.

May His great name be blessed forever and forever eternally.

Blessed and praised, glorified and exalted, extolled and honored, adored and lauded be the name of the Holy One; blessed be He who is high above, far above all blessings and hymns and praises and consolations, which are spoken in the world; and say, Amen.

May there be great peace from heaven and life for us and for all Israel; and say, Amen.

He who makes peace in the heavenly realms, may He make peace for us and for all Israel; and say, Amen.

(A leader recites the main portions, generally a mourner. The congregation responds with Amen.)

Because the mourner has been sitting on a low stool for a week, the ending of shiva is known as “getting up from shiva.” It marks the transition from the intense phase of grief into resuming their lives. Typically, mourners change clothes, put on regular shoes, go outside for the first time since the burial and take a walk, often accompanied by family or friends.

Sheloshim

Sheloshim is the next phase in Jewish mourning traditions. It lasts 30 days, beginning right after the burial, and includes the days of shiva. Some initial mourning restrictions are lifted during sheloshim, but some remain. Mourners still recite the Kaddish daily, and they are now allowed to change out of shiva clothes, wear leather shoes, go out of the house, sit on regular chairs, return to work and conduct business, use cosmetics, study Torah, and resume marital relations.

During the days of sheloshim, mourners are still not permitted to:

- Wear freshly laundered, new or ironed clothing

- Take luxurious baths or showers (but can shower quickly if they get dirty or sweaty)

- Get a haircut or shave

- Listen to music or participate in social events (with exceptions and special rules for certain religious or other significant events)

- Marry or engage in activities that do not fit with mourning (such as redecorating, remodeling or buying a home)

11 Months

After sheloshim, everyday life resumes for the mourner. However, if they have lost a parent, they are to say the Kaddish daily for a full 11 months from the burial day. This is seen as a way of observing the commandment to honor your father and mother. Jewish tradition claims that this recitation helps the deceased one’s spirit gain a more favorable status in the afterlife. In this belief, the more the Kaddish is spoken on behalf of the departed loved one, the more beneficial for them in the afterlife. This is considered a serious responsibility of the offspring left behind.

Yahrzeit

After the 11th month, mourners are no longer obliged to say the Kaddish for their parent until the exact anniversary of their death. Mourners then recite the Kaddish annually on the anniversary.

Jewish mourning traditions help us transition from losing a family member, and they also preserve the significance of national tragedies. As we practice them, we publicly recognize the immensity of our loss. In the case of Tisha B’Av, we mourn the loss of God’s holy Temple and outwardly express our sadness over so many horrific acts of anti-Semitism done toward our people over the millennia. Like personal mourning customs, Tisha B’Av joins our hearts around shared grief.

Jewish mourning traditions provide some unique means of traveling grief’s road, whether it concerns a loved one’s passing or a cultural history of tragedy and persecution. They pronounce the value of who and what was lost. They show us we are not alone and turn us toward the future with hope.